Playing Tag with the Sun

The Sun. It’s the star at the center of the Solar System, an almost perfectly spherical sphere of hot plasma that provides us heat and light almost 93 million miles away. Its heat is provided to us by nuclear fusion and radiates energy across the spectrum as visible light, ultraviolet light, and infrared radiation. Even though we see the Sun every day, there are still many things that we don’t know about the Sun. Previously, we have been able to answer some of these questions through telescopes and satellites orbiting Earth. But one satellite did something that is a first for exploration: it touched the Sun.

|

| Render of Parker Space Probe |

The Parker Solar Probe (abbreviated PSP; previously Solar Probe, Solar Probe Plus, or Solar Probe+) is a NASA space probe launched in 2018 with the mission of making observations of the outer corona of the Sun. It will approach within 9.86 solar radii (6.9 million km or 4.3 million miles) from the center of the Sun, and by 2025 will travel, at closest approach, as fast as 690,000 km/h (430,000 mph), or 0.064%of the speed of light.

The project was announced in the fiscal 2009 budget year. The cost of the project is US$1.5 billion. Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory designed and built the spacecraft, which was launched on 12 August 2018. It became the first NASA spacecraft named after a living person, honoring nonagenarian physicist Eugene Newman Parker, professor emeritus at the University of Chicago. The Parker Solar Probe concept originates in the 1958 report by the Fields and Particles Group (Committee 8 of the National Academy of Sciences' Space Science Board) which proposed several space missions including "a solar probe to pass inside the orbit of Mercury to study the particles and fields in the vicinity of the Sun". Having halved its distance to the sun since then, Parker Solar Probe has now identified one place where those features originate: the solar surface.

|

| Light Bar Testing of PSP |

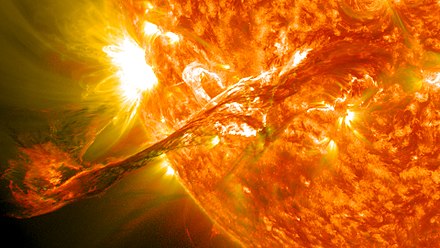

Even though Parker Solar Probe's solar panels — which provide the spacecraft's power — are retractable, the small bit of surface area that peeks out near the Sun is enough to make them prone to overheating. So, to keep its cool, Parker Solar Probe circulates a single gallon of water through the solar arrays. The water absorbs heat as it passes behind the arrays, then radiates that heat out into space as it flows into the spacecraft’s radiator. To perform its unprecedented investigations, the Parker Solar Probe and its instruments are protected from the Sun by a 4.5-inch-thick (11.43 cm) carbon-composite shield, which can withstand temperatures reaching nearly 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit (1,377 Celsius). But as dust grains pelt the spacecraft along its path, the high-velocity impacts create clouds of plasma. The spacecraft is flying closer to the Sun’s surface than any spacecraft before it. Parker will fly more than seven times closer to the Sun than any spacecraft. At its closest approach, the spacecraft will come within about 3.9 million miles (6.2 million kilometers) of the Sun. Mission scientists have used this data, for example, to construct comprehensive pictures of the structure and behavior of the large cloud of dust that swirls through the innermost solar system. Understanding the action of stars and their impact on planets is of particular interest to astronomers both for the knowledge we can gain and for predicting solar weather for the benefit of Earth and crewed space travel. The probe set out from Earth on an orbit that travels between the Sun and Venus, in turns. Each pass around Venus offers a gravitational assist, pushing Parker closer to the Sun’s surface. During a recent pass, which occurred in April of this year, the probe crossed an important boundary known as the Alfvén critical surface. The results of that pass were delivered in a paper written by Justin Kasper from BWX Technologies and the University of Michigan, and colleagues. It was published in Physical Review Letters. It has now circled the sun more than eight times and "touched" the sun for the first time when it entered the corona — the low density, high-temperature upper atmosphere of the sun — in April 2021, according to data published in Physical Review Letters on Tuesday. The probe's mission was to learn more about solar winds, which consist of streams of particles that influence the earth as well as magnetic zig-zags called switchbacks, and the sun's surface temperature. On Dec. 14, 2021, NASA announced that Parker had flown through the Sun’s upper atmosphere – the corona – and sampled particles and magnetic fields there. This marked the first time in history, a spacecraft had touched the Sun.

|

| Image Captured by PSP of the Sun |

Parker Solar Probe just completed its eighth close approach to the Sun, coming within a record 6.5 million miles (10.4 million kilometers) of the Sun’s surface on April 29. The team continues to track the spacecraft closely and will evaluate the necessity of other course-correction maneuvers over the next several months. Parker Solar Probe is healthy and its systems are operating normally. NASA's Parker Solar Probe is diving into the Sun’s atmosphere, facing brutal heat and radiation, on a mission to give humanity its first-ever sampling of a star’s atmosphere. The Parker Solar Probe has taken a multitude of energy-losing gravitational interactions with planets, especially repeated interactions with Venus, to enable it to get this close to the Sun. Its closest final approach, after continued gravitational interactions with Venus, will bring it to within 6.16 million km (3.83 million miles): by far the nearest we’ll ever have come to it. For comparison, the Voyager 1 spacecraft, launched back in 1977, is currently traveling at about 38,000 mph (61,000 km/h), according to NASA — less than 10 percent of the Parker Solar Probe's peak speed.

|

| Orbit of PSP |

When it slipped into orbit around Jupiter in July 2016, NASA's Juno probe briefly clocked in at 165,000 mph (266,000 km/h), making it the fastest spacecraft to date. That was achievable thanks, in part, to the gas giant's own gravity — which some sticklers claim is cheating. At about 10:54 p.m. EDT, Parker Solar Probe surpassed 153,454 miles per hour — as calculated by the mission team — making it the fastest-ever human-made object relative to the Sun. Parker Solar Probe will repeatedly break its own records, achieving a top speed of about 430,000 miles per hour in 2024. This breaks the record set by the German-American Helios 2 mission in April 1976. During its 7-year mission, it is expected to investigate, among other things, the details of solar flares. It is expected to make a total of 26 flybys, 10 of which have taken place so far.

Ultimately, the work being done by the Parker Solar Probe will help us learn about the sun in ways we never imagined we could. We are able to actually touch the Sun, something that we once never dreamed about. Space exploration and technology are hands in hand, the better we get at building new technology, we will be able to learn more about the universe.

|

| Render of Massive Solar Flare |

Citations:

Comments

Post a Comment